Slim Down for Safety: Even Roads Go on Diets

While many well-intentioned resolutions to slim down and shape up are broken within the first few weeks of the year, the type of diet we engineers are most familiar with is designed to extend well into the new year and beyond. Here are some insights into how (and why) engineers sometimes put roads on diets.

What’s a road diet?

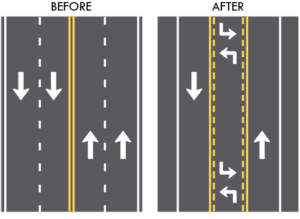

Road diets are exactly what the term implies. We’re reducing the number of travel lanes to make traffic flow more smoothly. In most cases we convert a four-lane roadway to a three-lane one – a travel lane in each direction with a middle lane to make left turns from.

It seems counterintuitive that going from four lanes to three makes traffic flow better. How does it work?

Incorporating a two-way left-turn lane, or TWLTL (pronounced “twittle” and rhymes with “whittle”) into the design allows us to reconfigure the roadway to make it safer. Instead of a standard 48-foot, four-lane roadway, we can convert it to two 11- to 12-foot lanes along with a 14- to 16-foot TWLTL. The extra width is then freed up for other uses, such as parking, sidewalks, landscaping, or bike lanes.

Road diets have been studied and studied again and repeatedly prove to reduce crashes. When you have a four-lane section, drivers tend to regard the left lane as a passing lane – as you’d see on an interstate. They’re not expecting vehicles to stop and turn left, and as a result you see a high frequency of rear-end crashes. Adding the TWLTL gets left-turning vehicles out of the through lanes so they’re not slowing down traffic as they prepare to make their turn. They’re also crossing fewer lanes of traffic when they do, which leaves them exposed for less time and eliminates the blind spots caused by multiple turning vehicles.

In what situations would one see a road diet in action?

Road diets are often in place in urban or suburban situations where there are higher concentrations of traffic and left-turn movements. We saw this at a project site on State Highway 27 in Hayward, Wisconsin, where a fast food restaurant, gas station, and grocery store are positioned on one side of the road and another gas station and convenience store are on the other. With so many motorists turning in and out of those areas, we’re designing a TWLTL to help manage traffic – setting up the entrances so we no longer have multiple travelers trying to cross at conflicting points. Soon drivers from both directions will be able to make left turns at the same time without impeding visibility or bottlenecking traffic flow at the crossing.

Road diets are often in place in urban or suburban situations where there are higher concentrations of traffic and left-turn movements. We saw this at a project site on State Highway 27 in Hayward, Wisconsin, where a fast food restaurant, gas station, and grocery store are positioned on one side of the road and another gas station and convenience store are on the other. With so many motorists turning in and out of those areas, we’re designing a TWLTL to help manage traffic – setting up the entrances so we no longer have multiple travelers trying to cross at conflicting points. Soon drivers from both directions will be able to make left turns at the same time without impeding visibility or bottlenecking traffic flow at the crossing.

What factors do engineers consider when evaluating a roadway for a possible diet?

We weigh several considerations when evaluating a potential road diet scenario, including:

1. Average daily traffic in peak hours. If you don’t have high volumes of traffic on a particular stretch of road, you might consider reducing the number of lanes.

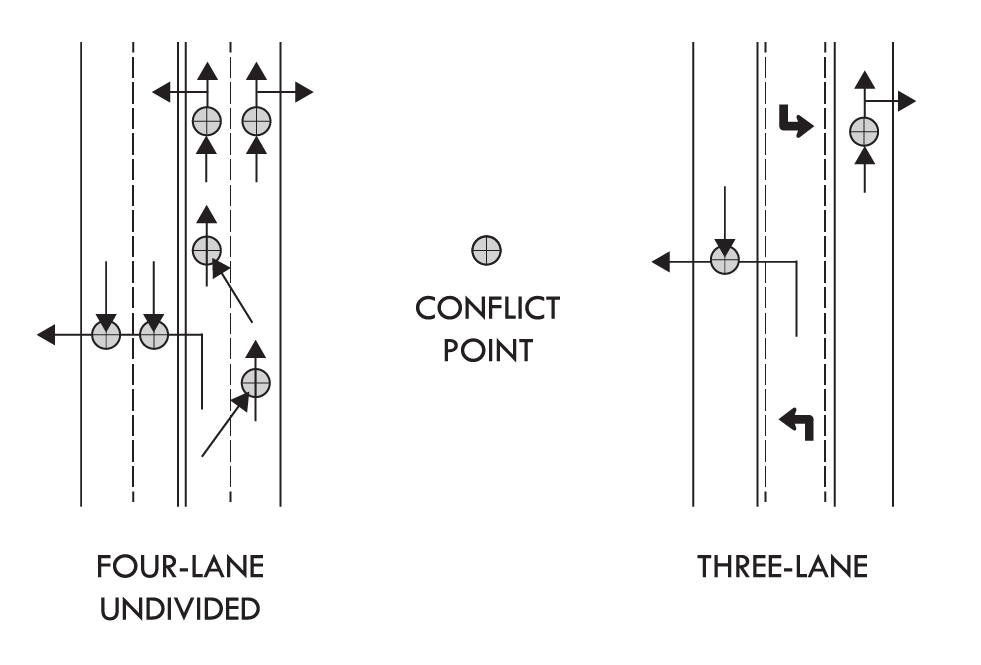

2. Crash rates. Left-turn crashes and rear-end collisions often result from drivers stopped to make a left turn into a driveway or side street. In an urban area, you may not have room to purchase right-of-way to make the left-turn lane, which is one of the natural strategies to address a left-turn issue that’s producing rear-end crashes. A road diet allows you to reduce the number of potential conflict points along the street and at intersections – for example, creating a left-turn area where people can safely stop as they wait for a gap in opposing traffic. Before a diet, there might be six conflict points on a four-lane street between cars turning and merging. Afterwards, only two potential conflicts remain.

3. Community requests for bicycle accommodations or on-street parking. Road diets allow you to carve out a space for a bicycle lane or, depending on the width of the road, a parking area.

More times than not, safety is the impetus behind implementing a road diet. We’re purposely slowing down traffic to reduce the speed differential between vehicles, cut down on the number and severity of crashes, and protect vulnerable road users such as bicyclists, pedestrians, and other recreational users. (This new center area also provides an area where a raised median can be placed to shelter them.) And forcing traffic to travel in a single lane tends to self-regulate traffic speeds a little bit. Therefore, any crashes that do occur are going to be less severe.

Road diets are one of many strategies we have available to manage – and tame – traffic. Read on for more information on the important part road diets play in managing traffic flow and the additional advantages they bring to communities.

Road diets are one of many strategies we have available to manage – and tame – traffic. Read on for more information on the important part road diets play in managing traffic flow and the additional advantages they bring to communities.

Mark Petersen is a transportation engineer in Ayres’ Eau Claire, Wisconsin, office. His primary responsibilities include project management, urban and rural state highway design, report preparation, utility coordination, and agency coordination.

Post a comment: