One-Way or the Other? Two-Way Traffic Conversion Requires Study

A drive through the downtown area of many American cities includes time spent on one-way streets. Cities have used short segments of one-way traffic for hundreds of years to try to improve traffic flow and move higher volumes of traffic along downtown arterials. However, in recent years many communities have begun to ask if these one-way “couplets,” which became popular in the middle of the 20th century, are the best way to serve downtown visitors and businesses. They are considering restoring these streets to two-way operation.

About the Expert:

Alexander Cowan, PE, PTOE, is a traffic engineer based in our Waukesha, Wisconsin, office. He has over 14 years of experience in intersection and signal design, traffic analysis, and transportation management plans. Alexander specializes in microsimulation modeling.

A thorough evaluation is needed whenever these restorations are considered, as the characteristics of the roadway and the goals of the local stakeholders are not the same in every location. Traffic consultants provide the needed reality checks as communities look to two-way conversion as one of the ways to refocus and revitalize their downtown corridors.

One-Way History Dates Back 400 Years

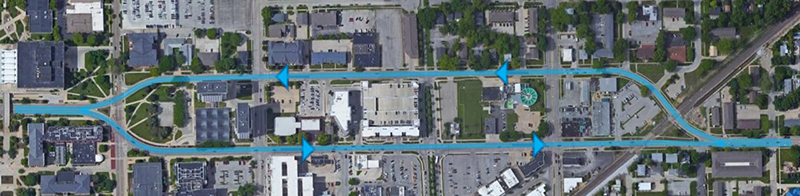

One of the earliest documented examples of a one-way street can be found in London in the early 17th century. Apparently, horse-drawn carts and buggies were not immune to the congestion problems that still plague our transportation system 400 years later. More recently, one-way streets were implemented in many busy downtown corridors in the United States. In many cases the main downtown roadway was split off into a pair of one-way streets, mirroring one another with a string of shops and restaurants separated by a block or two in between. The practice became common throughout the mid-20th century as more and more people moved to the suburbs, and moving traffic efficiently along downtown arterials became a higher priority.

In recent years as downtown and urban areas are revitalized and pedestrian and bicycle traffic in these areas increases, many communities are re-evaluating the idea of one-way couplets. Should these corridors serve as a highway to shuttle cars through downtown as efficiently as possible, or as a welcoming gateway to the heart and soul of a community? Restoring one-way streets to two-way operation in downtown locations can refocus the purpose of these busy corridors, zeroing in on easier local access and improved circulation. But many different factors impact whether restoration is a good idea.

One-way streets are generally seen as making access to any particular location less convenient, as vehicles often need to circulate around the block to reach their destination, which can contribute to lower exposure for businesses and increased driver confusion. Two-way streets, often designed with one lane in each direction, bring challenges with delivery access for trucks that can often get away with double-parking on a one-way street but not on a two-way. Pedestrians can find crossing two directions of traffic less comfortable than one-way. On the other hand, the traffic calming effect attributed to two-way traffic may mitigate this concern.

One-way streets are generally seen as making access to any particular location less convenient, as vehicles often need to circulate around the block to reach their destination, which can contribute to lower exposure for businesses and increased driver confusion. Two-way streets, often designed with one lane in each direction, bring challenges with delivery access for trucks that can often get away with double-parking on a one-way street but not on a two-way. Pedestrians can find crossing two directions of traffic less comfortable than one-way. On the other hand, the traffic calming effect attributed to two-way traffic may mitigate this concern.

We’ll try to untangle this web of pros and cons and explain how a two-way restoration feasibility study can help to identify the appropriate traffic configuration for a wide range of communities.

We’ll try to untangle this web of pros and cons and explain how a two-way restoration feasibility study can help to identify the appropriate traffic configuration for a wide range of communities.

What Are the Pros and Cons of One-Way and Two-Way Traffic?

One of the purposes of downtown streets is to move people and goods safely and efficiently. One-way couplets generally are able to move a larger number of vehicles through a corridor with less delay, as there are fewer movements to accommodate at each intersection, and it’s possible to move a larger platoon of vehicles through a green light at a signalized intersection if those vehicles are all pointed in the same direction. Two-way streets have the potential to increase travel times and reduce speeds – perhaps bad news for through traffic but good news for other users of the street, such as pedestrians and bicyclists.

It’s important that a thorough traffic operations analysis be completed to ensure that a two-way restoration will still provide acceptable operating conditions.

With respect to safety, one-way streets reduce the number of conflict points within intersections and require that pedestrians concern themselves with only one direction of traffic when crossing a street. On the other hand, two-way streets often reduce travel speeds, making the effort of crossing the street more comfortable for pedestrians. A two-way street is likely to result in fewer lanes in a given direction, thereby reducing the chances of an oncoming vehicle “hiding” behind another car in the adjacent lane. Slower speeds mean vehicles have more reaction time to avoid collisions, and when crashes do occur, they are less likely to cause an injury or fatality. Two-way streets also reduce the incidence of wrong-way drivers causing head-on crashes.

With respect to safety, one-way streets reduce the number of conflict points within intersections and require that pedestrians concern themselves with only one direction of traffic when crossing a street. On the other hand, two-way streets often reduce travel speeds, making the effort of crossing the street more comfortable for pedestrians. A two-way street is likely to result in fewer lanes in a given direction, thereby reducing the chances of an oncoming vehicle “hiding” behind another car in the adjacent lane. Slower speeds mean vehicles have more reaction time to avoid collisions, and when crashes do occur, they are less likely to cause an injury or fatality. Two-way streets also reduce the incidence of wrong-way drivers causing head-on crashes.

Besides the critical concerns of operations and safety, determining whether converting from one-way to two-way is a good idea involves evaluating many considerations:

Besides the critical concerns of operations and safety, determining whether converting from one-way to two-way is a good idea involves evaluating many considerations:

- Business exposure/visibility: Slower traffic under a two-way street configuration means motorists have more opportunity to notice businesses, parks, and attractions. Two directions of travel provide for two different perspectives and opportunities to notice the local community. However, traffic could also decrease if the speeds are so slow that drivers choose a different route.

- Complex intersections: Many couplets feature complex intersections at the ends of the corridor, sometimes with five or six legs. Some downtown corridors with angled streets include awkward, nonstandard intersections. Introducing two-way traffic at these unique intersections may require creative solutions and alternatives for accommodating traffic.

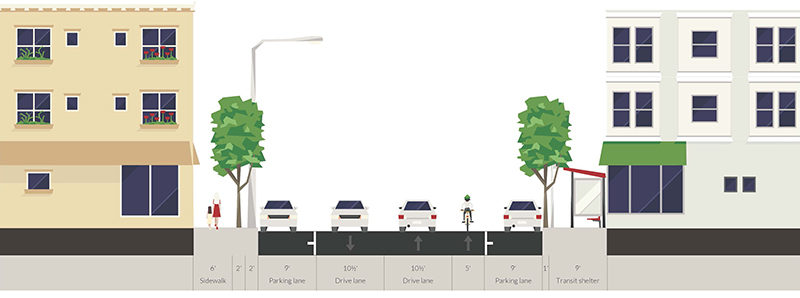

- On-street parking: Parking near intersections may need to be removed to accommodate a turn lane. Conversely, parking could increase if analysis shows reserve capacity is available for parallel or angle street parking.

Additional considerations may include:

- Impacts on parallel routes

- Restrictions on intersection turning movements

- Bus stops, streetcars, light rail, and other transit considerations

- Pedestrian bump-outs and refuge islands

- Loading zones vs. double parking for truck deliveries

- Restrictions on heavy vehicle traffic

- Bicycle accommodations

Public involvement is essential in making a decision that will have very concrete impacts on users. The decision to implement a one-way or two-way roadway requires tradeoffs, and understanding the priorities of the public allows the evaluation study to appropriately weigh the potential impacts. If it is decided that streets will be converted to two-way flow, new signage and pavement marking must be designed, and phasing must be determined. Ultimately a city must decide on the proper timing for “flipping the switch” to two-way flow – sometime overnight or during off-peak daytime hours. The new traffic patterns and the phasing of implementation must be clearly communicated to the streets’ users.

With a high-quality study in hand, communities can move forward confidently, ready to improve their downtown district for businesses, residents, and a wider range of roadway users.

With a high-quality study in hand, communities can move forward confidently, ready to improve their downtown district for businesses, residents, and a wider range of roadway users.

Alexander Cowan, PE has assisted numerous communities in evaluating the feasibility – and overcoming the challenges – of restoring one-way couplets to two-way operation. Check out the project experience of our traffic engineering and analysis staff on a wide range of highway, municipal, and development projects.

By

By

Post a comment: