Highways Designed with Snow and Cold in Mind

From temperature extremes to drainage, roadway designers factor in the snow and cold when designing for our northern and mountain states. Let’s look at the properties of various pavement types and the basics of how that pavement is placed and treated for optimal performance in climates plagued by cold and snow.

About the Expert:

Eric Sorensen, PE, is the vice president of Ayres’ Midwest transportation operations. He oversees transportation and traffic engineering and construction services in the Midwest. He has extensive experience managing and designing transportation-related projects for the State of Wisconsin and local governments. His experience includes project coordination with government and local agencies, and he has served as a resident engineer for construction observation projects.

Temperature Extremes

Because pavement expands in the summer heat and contracts in winter’s cold, it’s important to realize that asphalt pavement is considered a flexible pavement while concrete is rigid. To account for concrete’s expansion and contraction, sawed joints must be installed at approximately 15-foot intervals to reduce the potential for summer concrete heaving resulting from slab expansion. Winter can wreak havoc on concrete patches when water gets into cracks around patches and starts to freeze and thaw. This causes the patch to move around and loosen. As traffic continues to travel over the patch, it can become loose and pop out of the pavement, causing safety concerns. This has occurred during an extreme cold snap in a past December outside Madison, Wisconsin, closing two westbound lanes on the USH 12/18 Beltline.

Asphalt is less susceptible to buckling, but it is important to use the correct recipe when mixing asphalt for use in various climates to reduce the incidence of rutting and cracking. Performance grading (PG) specifications for asphalt take climate into account, calling for a different type of binder (oil) in regions that experience extreme cold versus ones that have milder winter temperatures. The specifications also vary based on how wildly pavement temperature varies from summer to winter. The formulations of asphalt pavement are numerous.

Asphalt is less susceptible to buckling, but it is important to use the correct recipe when mixing asphalt for use in various climates to reduce the incidence of rutting and cracking. Performance grading (PG) specifications for asphalt take climate into account, calling for a different type of binder (oil) in regions that experience extreme cold versus ones that have milder winter temperatures. The specifications also vary based on how wildly pavement temperature varies from summer to winter. The formulations of asphalt pavement are numerous.

Even within Wisconsin, two different binder types are used, with one known as the “Northern Asphalt Zone,” where the pavement temperature range is judged to be 58 Celsius to -34 Celsius (136 to -29 Fahrenheit). The pavement specification for various temperature ranges is designed to retain enough rigidity at the highest temperatures to resist rutting while retaining enough flexibility at the lowest temperatures to resist thermal cracking.

A highway through the Rocky Mountains could potentially require multiple asphalt formulations accounting for stretches that lie in several different climates from low elevation to high. Rutting due to studded tires and tire chains also can have an impact on mountain roadways.

A Matter of Drainage

Porous pavement has been found to perform well in cold climates, promoting faster melting and drainage, reducing the amount of salting needed, and providing better wet-weather grip, according to this Wisconsin Asphalt Pavement Association article.

In areas with soils susceptible to frost heave, PVC drain piping and a layer of well-draining gravel under the surface pavement can tame heaving.

Other Factors Distinguishing Concrete from Asphalt

Concrete is also known to be more susceptible to certain de-icing agents, especially if applied within the first six months after the concrete is poured. A Brigham Young University report for the Utah Department of Transportation concluded the type of de-icer is critical in determining how much damage is done to concrete pavement over the course of a winter. “Engineers responsible for winter maintenance of concrete pavements should utilize sodium chloride whenever possible, instead of calcium chloride, magnesium chloride, or CMA,” the report concluded.

Another straightforward and observable difference between asphalt pavement and concrete is that the dark color of asphalt early in its life cycle leads to faster snow and ice melting due to simple solar heating of the pavement, but this factor is not typically given much weight in deciding which pavement to use in a particular location. However, consideration is given to the removal of trees that shade roadways in winter, slowing the melting of snow and ice.

Fence a Good Way to Play Defense

Another low-tech measure that can actually keep snow from landing on a road in the first place involves snow fencing. A snow fence placed upwind from a roadway slows drifting snow, depositing it on the leeward side of the fence (between the fence and the road) instead of allowing the blowing snow to be deposited on the road. Strategic plantings can accomplish the same thing. A snow fence or plantings should be placed at a distance from the road that is at least 35 times the height of the fence or plantings, according to U.S. Netting.

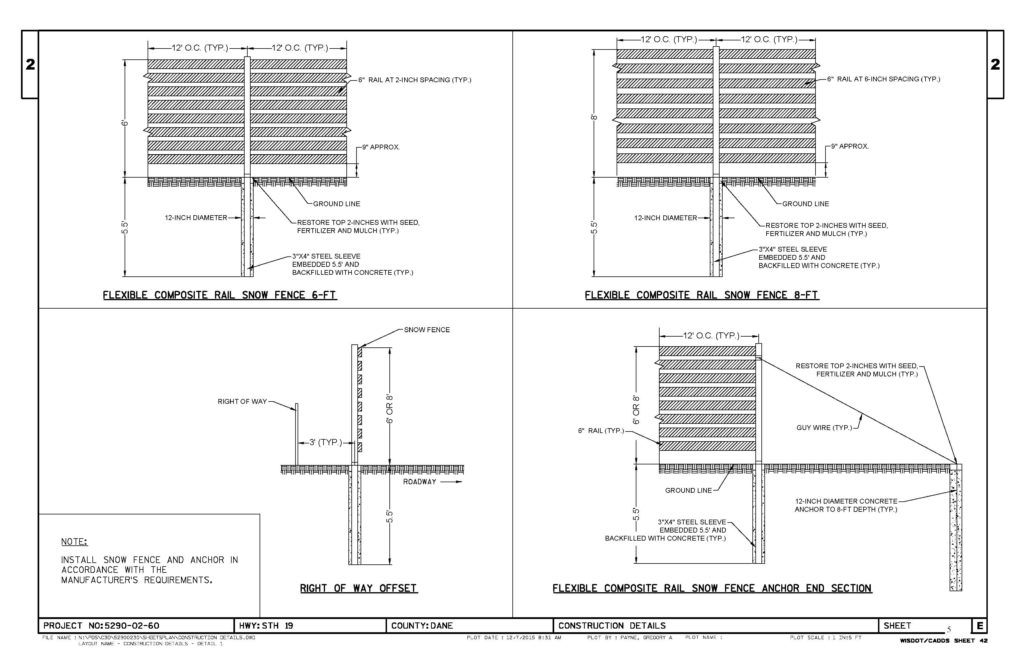

Snow fencing is often erected seasonally, but a Wisconsin Department of Transportation project along STH 19 north of Madison specifically addressed snow drifting and slippery pavement on a stretch that had higher-than-normal winter accident rates by building permanent snow fences and applying a new friction surface treatment to the roadway. The fence (plan sheet shown here) consists of metal poles with thin horizontal strips extending between the poles.

Road Slope and Bridge Design

Even the designed pitch of a roadway has to take into account the possibility of icy or snowy surfaces. Generally a rural roadway cross slope – such as a banked curve — is desired to be no more than 5% to minimize the chance that a car that is traveling slowly or waiting to turn left onto an intersecting road would slide sideways down the cross slope and into oncoming traffic.

Bridge design also takes winter into account, such that bar steel in bridge decks has a protective coating (accounting for the name “green bar”) to resist premature corrosion from road salt. Bridge decks and parapet surfaces also are treated with a protective coating, and long, curved bridges are treated with an anti-skid surface treatment to provide more traction. Bridges often freeze before surrounding roadway segments because of the air circulation under them, catching motorists off guard with icy spots on otherwise wet roads.

Contact Ayres’ roadway design team to learn more about how they can help with your road design, construction, and rehabilitation needs.

Looking for a Chance to Define Your Career Path?

Our St. Paul office is looking for a bright-minded leader to create and manage a Transportation Engineering/Design group! Take advantage of this unique opportunity to grow a team of professionals while writing your own story within Ayres.

Post a comment: